We had a Facebook follower ask for the rotary engine equivalent to a story we did a couple weeks ago on piston design. This is a bit of a tricky request, since the way a rotor works within a rotary engine isn’t quite the same as the way a piston works, so rather than just discuss how the rotor functions within the combustion cycle, I’ve decided to go full-geek on the subject and cover the rotary engine from top to bottom.

Now, if you’re a Japanese performance car enthusiasts chances are you’re at least somewhat familiar with the 13B two-rotor engine Mazda equipped the RX-7 and RX-8 with. But unless you’ve owned and modified a RX of some type, then you may only have a basic understanding of how this unique type of combustion engine differs from a more traditional piston engine. If the name Dr. Felix Wankel means nothing to you, then here’s your chance to learn everything you ever wanted to know about rotary engines. Read this epic tale in its entirety and you may even fall in love with this ingenious engine design and find yourself looking at rotary-powered Mazdas in a whole new light.

The history of the rotary engine is a strange and wonderful tale that dates back as far as 1588 when Ramelli invented the first rotary piston type water pump. Almost two hundred years later James Watt, a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer whose pioneering work with steam engines helped drive the Industrial Revolution, invented the first rotary steam engine in 1769. So although we motorheads (and rotorheads) tend to give Dr. Felix Wankel (1902-1988) sole credit as the inventor of the rotary engine, the truth is that rotary engine design goes back much further than this 20th century German engineer.

Still, Wankel’s story is a fascinating one. His obsession with the idea of building a rotary engine began in 1919 when, at the ripe old age of 17, he had a strangely prophetic dream that he invented an engine that was half-turbine half-reciprocating in design. With no formal training (he was granted an honorary Doctorate later in life), Wankel set up his own research lab at the age of 22 and began pursuing his dream. Fast-forward to WWII when, as a member of the Nazi party, Wankel continued his work with the support of the German Aviation Ministry and private funding from the corporate sector, both of which believed that the development of a rotary engine would give the nation and its industries an advantage over its enemies.

The DKM, designed by Dr. Felix Wankel and manufactured by automaker NSU, was the first working prototype.

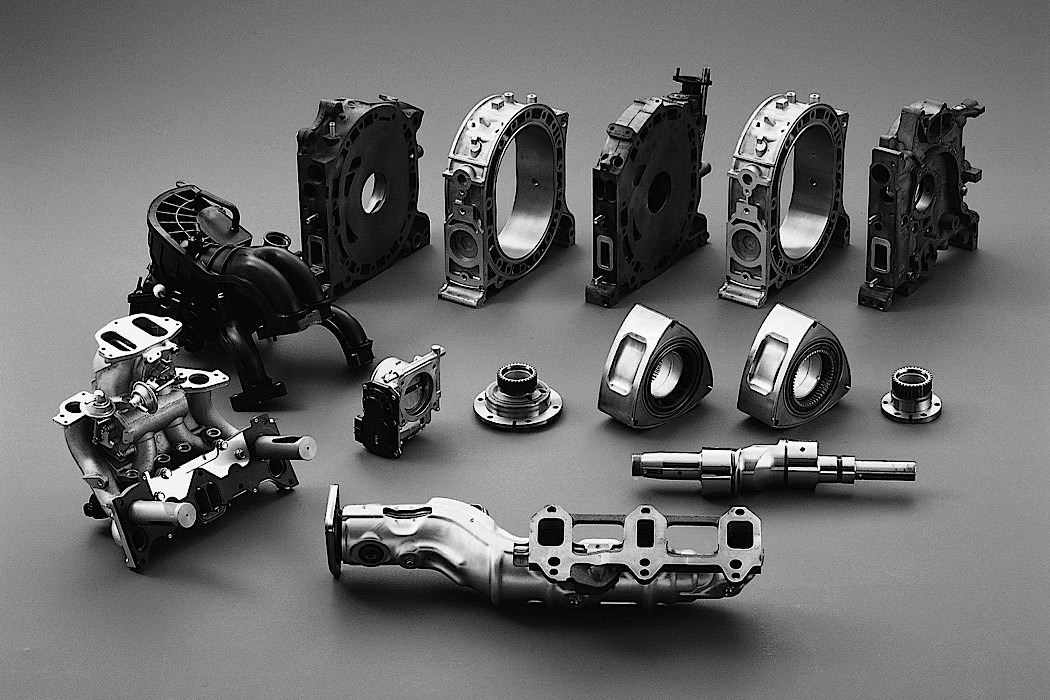

After the war Wankel was eventually able to reestablish himself (having been imprisoned for a short time by the Allies, his lab closed and research confiscated), starting the Technical Institute of Engineering Study where he continued his rotary engine R&D. Shortly after, in 1951, Wankel partnered with motorcycle and car manufacturer NSU and just six years later Wankel and NSU completed a prototype rotary engine called the DKM. This first working prototype used a rotating cocoon-shaped rotor housing and a triangular rotor, but it was the KKM with its static rotor housing – completed a year later in 1958 – that’s considered the true forefather of the modern rotary engine.

It wasn’t until 1963 that the first rotary-powered car hit the streets as a 1964 model year NSU Wankel-Spider. Then, in 1967, NSU released the Ro-80 sedan with a two-rotor 113-hp Wankel engine and earned ‘Car Of The Year’ accolades in the European press. But because of the extremely costly development of the rotary engine and damage done to the brand’s reputation by rotor apex seal reliability problems, NSU was taken over by the Volkswagen Group in 1969 (who merged NSU with Auto Union to form Audi) and the use of Wankel rotary engines was phased out.

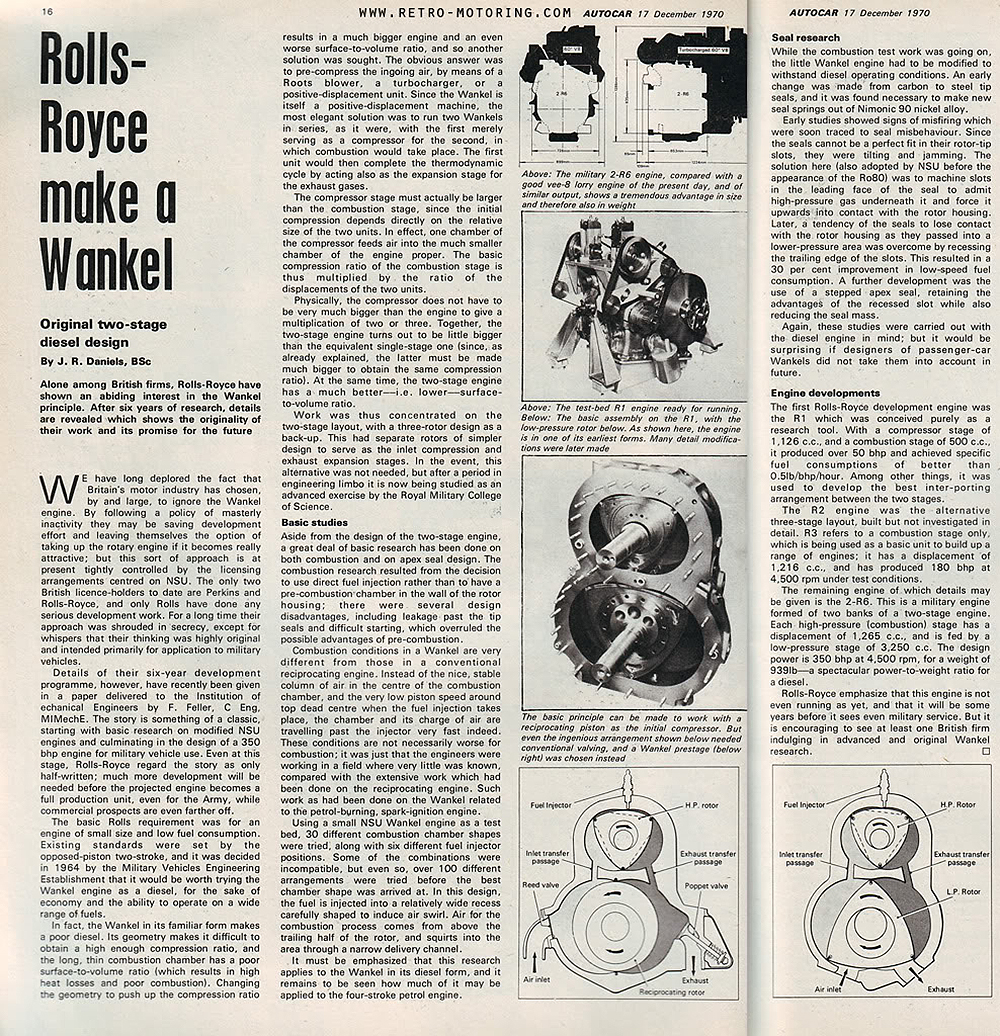

But before NSU’s merger with Auto Union, as joint patent-holders Dr. Wankel and NSU sold licenses to other automakers to develop their own versions of the rotary engine. Most major automakers bought a license during the 1960s and began rotary engine development programs of their own (the smooth and quiet operation and fewer moving parts of a rotary engine having strong appeal), Rolls Royce and General Motors among them. But as you know, it was the relatively small Japanese car company by the name of Mazda that eventually emerged as the only automaker able to mass-produce reliable and cost-effective versions of Wankel’s design.

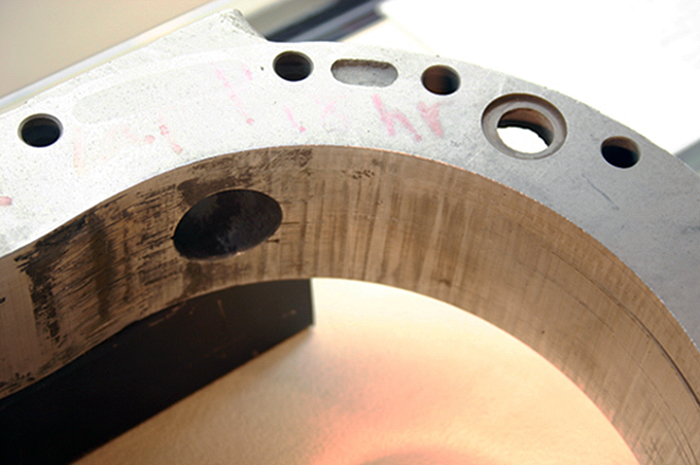

Mazda’s journey into the world of rotary engines began in 1961 when then president Tsuneji Matsuda personally negotiated a licensing agreement with NSU. As part of this agreement Mazda obtained a prototype of an NSU-built single-rotor engine and first learned of the “chatter mark” problem. These chatter marks, something Mazda’s engineers nicknamed “nail marks of the Devil”, presented themselves as wavy traces of abnormal wear on the rotor housing, causing the seals and the housing itself to significantly deteriorate. This was a major roadblock to the practical and widespread use of rotary engines and it was Mazda’s own engineers – having formed its RE (Rotary Engine) Research Department – that eventually solved the problem.

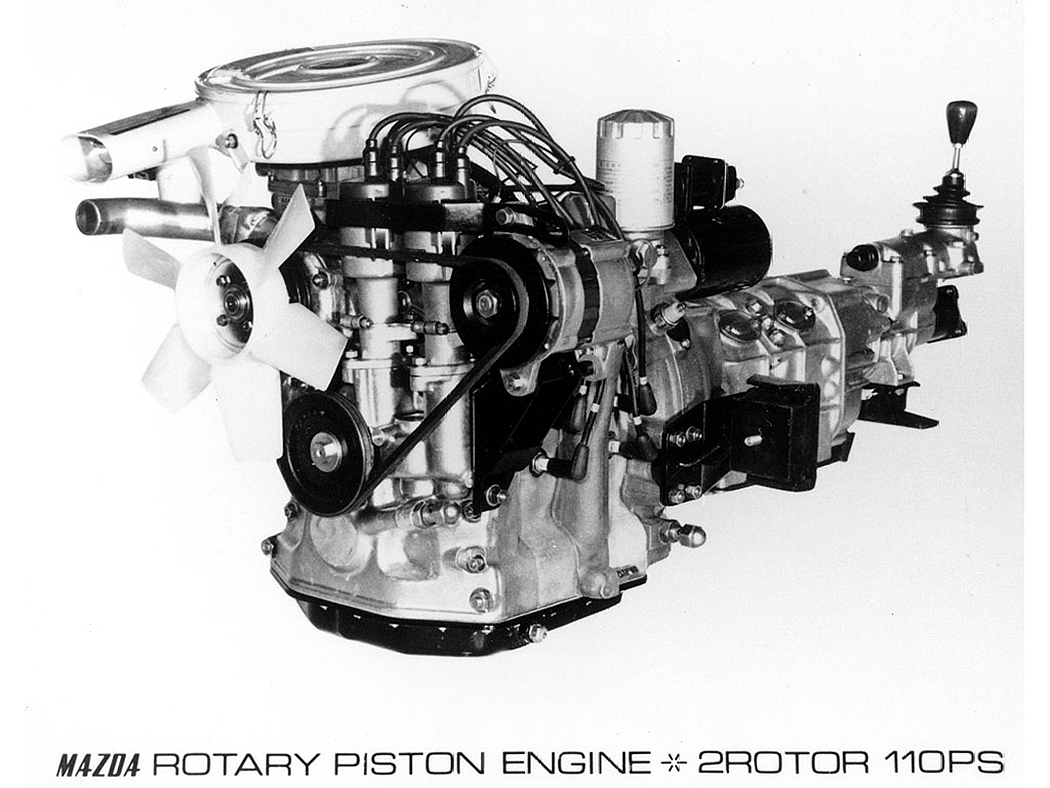

Recognizing the limitations (and in particular the lack of low end torque) of a single rotor engine design, Mazda began investigating two-rotor, three-rotor and four-rotor designs while working on solving the apex seal vibration issue causing the chatter marks and the oil consumption problem caused by a leaky oil seal. Just three years after signing the licensing agreement with Wankel/NSU, their second two-rotor test engine, called the Type 3820 (2 x 491cc), was built. This engine evolved into the 10A mass-production two-rotor engine featured in the now famous and highly collectible 1967 Mazda Cosmo Sports.

Pumping out 110-hp, the 10A two-rotor engine was equipped with newly developed high-strength carbon-based apex seals that showed only slight wear and none of the dreaded chatter marks after 100,000 km of testing. It would seem that Mazda had solved the dreaded “nail marks of the Devil” and had also cured the oil consumption issue by developing a unique oil seal in conjunction with the Nippon Piston Ring Co. and Nippon Oil Seal Co.

Awesome post! Great insight into Jim Mederer’s rotary tuning.

BrianCan I concur, although I fear that I am biased towards the Rotary engine 🙂

Excellent write up as always !