Rotors or disc brakes aren’t the sexiest part of a car, but if you’ve got enough track days under your belt then you’ve probably learned the hard way that not all rotors are created equal and that rotor performance is hugely important if your goal is to have a reliable and consistent brake pedal under your foot. I can remember a disappointing Time Attack event in Montreal where we cracked a rotor on my dad’s ’97 Camaro Z/28 and had to pack up early. The OEM rotors on that car simply weren’t up for the thermal stress we were throwing at them at the race track.

These days high-performance rotors are incredibly advanced. I’m sure you’ve all seen carbon-ceramic rotors on high-end sports cars and even carbon-carbon rotors on full blown race cars. How do these materials alter the performance of the braking system compared to good old cast iron discs? How does the internal vane structure improve performance? How does a two-piece floating disc perform compared to a 1-piece? And what’s the deal with all the different slot shapes and frequencies on the disc face? Thanks to technical insights provided by Mark Vlaskis from Brembo North America and Yoni Kellman from DBA USA, we’ll cover all these topics so you can make a more informed purchase.

As most of you already know, the main job of the rotor is to provide a mating surface for the brake pads so that when you apply the brakes the friction material that makes up the pad is hydraulically squeezed against the rotors by the brake calipers, converting forward motion into heat as the car is slowed. This heat is then radiated to the atmosphere as air flows over and through the rotors (and the rest of the braking system), completing the conversion of kinetic energy into thermal energy. And as the largest mass in the braking system, the disc plays a vital roll in absorbing and shedding all that heat.

DBA 4000 Series one-piece rotor

I’ve done most of my racing in relatively small, lightweight, and low to medium power vehicles like Hondas, Mazdas and Scions, so for my needs I’ve mostly been able to use high-quality one-piece cast iron brake discs without issue. But with my big, fat Infiniti G35 coupe, stepping up to larger diameter two-piece rotors completely transformed the car’s performance. As Yoni from DBA USA explained, “From a cost perspective, a one-piece rotor is able to meet the needs of most drivers in most cases and is cost effective, particularly when the rotor uses high-quality materials and design and is paired with appropriate pads for the intended use of the vehicle.

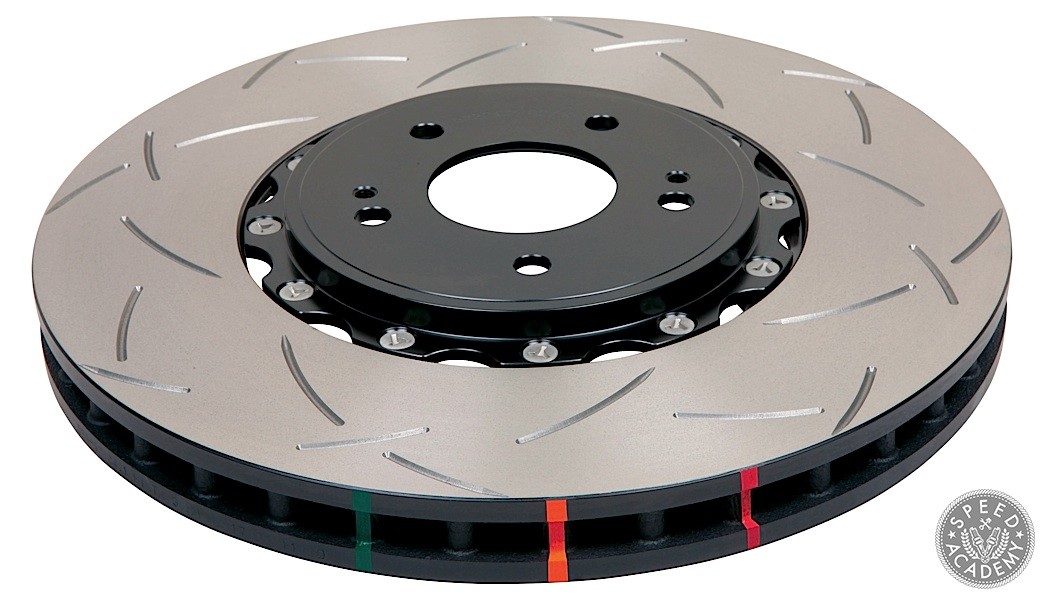

Two-piece rotors offer some significant advantages, though, such as reduced weight as well as better heat dissipation, partly from the aluminum hat acting as a heat sink. Some two-piece rotors also offer increased airflow through the rotor because of the more open design where the hat meets the rotor face. Another big advantage is the ability to replace only the disc ring while reusing the center hat. This can add up to cost savings in many cases.”

Brembo two-piece floating rotor

As Mark from Brembo added, “There really are no downsides to two-piece construction other than cost. The first advantage of floating 2-piece construction is reduced weight. By making the center-section of the disc out of aluminum, a great deal of weight can be saved in a key location, as it is both unsprung and rotating. Another advantage to this construction is reduced heat-transfer to the vehicle’s hub and wheel bearings. While overheating wheel bearings in street-use isn’t normally a concern, it certainly can be when driving on the racetrack. But the greatest advantage lies in the float itself. The brake discs must cope with extreme temperature levels. In some cases, the disc temperatures can exceed 1100°F. When a material is heated it expands, and due to the large temperature change experienced in brake discs, this effect can be significant. In the case of a non-floating disc, not all of the material heats up uniformly. The center-section of the disc remains relatively cool compared to the braking surfaces. This temperature difference causes thermal stresses to develop which lead to warping of the disc and cupping of the braking surface, as well as increased crack potential. With the full-floating system, the disc is free to grow relative to the bell, and can remain straight and true.”

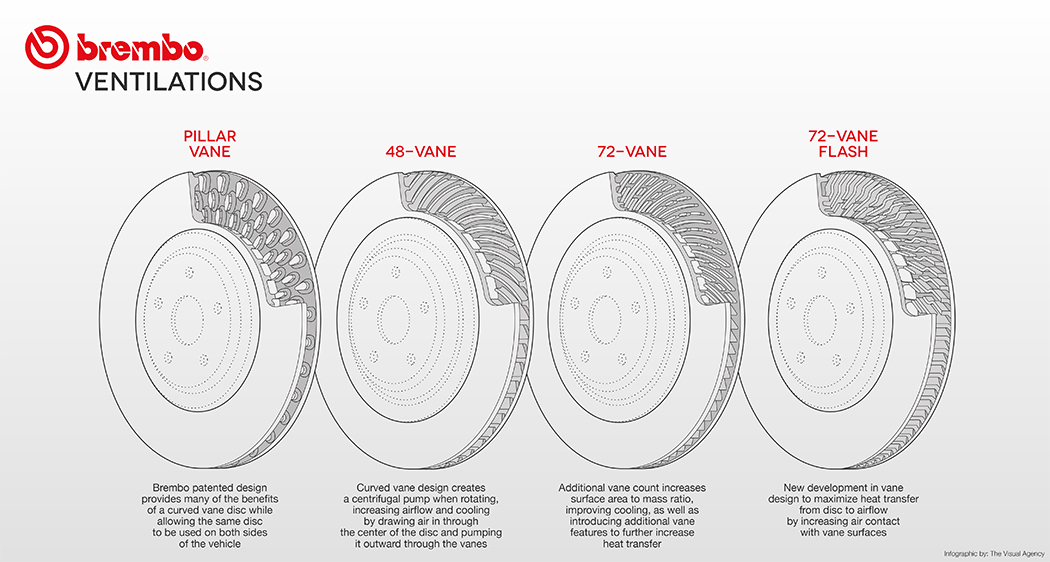

Another key element to rotor design is its internal vane design. As Mark from Brembo pointed out, “There isn’t one optimal vane design, it can vary depending on application. Some designs, such as directional curved-vane discs actually improve the airflow through the disc by turning it into a centrifugal pump. However, the cost of implementing this is increased due to the need for unique left- and right-hand discs. Brembo patented pillar vane internal geometry provides nearly all the airflow advantages of the curved vane discs while being able to use the same disc on both the left and right sides of the vehicle. Regardless of design, the vanes play an important factor in enabling the disc to shed heat and thus keep the disc within the temperature range dictated by the overall composition of the braking system (i.e. caliper, brake pad, brake fluid, etc), while being efficient in doing so from a weight and structural integrity standpoint.”

Yoni from DBA echoed the fact that there are many different philosophies for vane design. “In our case, we wanted to achieve two things when we came up with our patented Kangaroo Paw ventilation design. First was a high surface area for the most efficient heat dissipation as air travels through the rotor. Second was high strength. By using the specially distributed pillars and posts in our Kangaroo Paw design the load placed on the rotor during braking and heat changes is well distributed which reduces rotor distortion, and reduces ballooning which is a common problem with straight vane rotors and some curved vane designs as well.”

I’ve been needing to get some new disc brakes for my wife’s car. I’m glad you talked about different rotor designs for disc brakes, which I think is interesting. I’m going to have to look into a few god disc brake services and see what we can get!